Navy Seaman 1st Class James Richard Ward only had moments to decide what to do on the sinking USS Oklahoma during the bombing of Pearl Harbor: save himself, or do what he could to save others? Ward chose the valiant option, giving his life so his fellow sailors could escape. He earned a posthumous Medal of Honor for his gallantry, and just recently, his remains were finally accounted for and buried.

Ward was born Sept. 10, 1921, in Springfield, Ohio, to parents Howard and Nancy Ward. He had a sister named Marjorie.

According a 2014 Dayton Daily News article, as a teen, Ward, who went by the nickname Dick, did odd jobs for his neighbors to earn some cash. He played football and the trumpet, but his real love was baseball. After graduating high school in 1939, the article said Ward took a factory job before landing a minor league baseball contract with the Shelby Colonels out of North Carolina. However, the gig only lasted a month before he was replaced. Ward then worked at a steel mill for a time before enlisting in the Navy on Nov. 25, 1940.

After basic training, Ward was sent to serve on the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Hawaii. Since baseball was a huge pastime for service members, he was able to join the ship’s team. Ward helped them win the Pacific Fleet championship, and he was even named top batter.

Unfortunately, Ward would not live to see beyond the opening moments of the United States’ entry into World War II.

A Pivotal Decision

In the early morning hours of Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Oahu, surprising installations all over the island. The Pacific Fleet’s ships that were moored at Pearl Harbor’s Ford Island took the brunt of the assault, including the Oklahoma. In the first few minutes of the attack, the ship was hit by as many as nine aerial torpedoes, which ripped open more than 250 feet of hull on the ship’s port side. The massive amount of damage caused the Oklahoma to roll over and sink in less than 20 minutes.

Ward was in one of the ship’s turrets, which lost electricity immediately, leaving him and his fellow sailors in darkness. According to the Dayton Daily News, Ward was the only one in that turret with a flashlight.

When the order was given to abandon ship, Ward stayed in his turret, using the flashlight to allow the remainder of the crew to see to escape. While many of them made it out of the turret, Ward did not. At 20 years old, he sacrificed his own life for the lives of his fellow sailors.

All told, the Oklahoma lost 429 men that day. Thirty-two men who had been trapped inside its upturned hull were rescued days later.

In the aftermath of the attacks, it took a while for official death notices to go out. According to the Dayton Daily News, Ward’s parents didn’t learn of his official death until Feb. 20, 1942.

Despite the chaos of that fateful day, Ward’s valor didn’t go unnoticed. He was quickly nominated for the Medal of Honor, which was mailed to his parents in Springfield in March 1942, along with a letter from President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Navy Secretary Frank Knox.

A Long Journey Home

In 1943, the capsized Oklahoma was rolled upright and raised in one of the salvage profession’s greatest undertakings, naval historians said. Throughout the war, Navy personnel worked to recover the remains of the men who died inside the ship and bury them in temporary Hawaiian cemeteries.

After the war, the American Graves Registration Service was created to carry out a new mission — to identify and recover our fallen service members from around the globe. AGRS members disinterred the remains of the men from the Oklahoma and transferred them to an Army laboratory, which confirmed the identities of 35 men at that time. The rest of the remains were buried in plots at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu. By 1949, a military board classified those who hadn’t been identified as “nonrecoverable,” including Ward.

Nearly a lifetime went by before that changed.

In 2015, investigators – now with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency – exhumed the comingled remains of the buried unknown men from the Oklahoma to run tests using dental, anthropological and mitochondrial DNA analysis in the hope of finally identifying them. The agency compared those findings to DNA samples that had been provided years earlier by the 394 families of those who were never identified from the Oklahoma.

On Aug. 19, 2021, the DPAA announced it had finally accounted for Ward’s remains. He was buried last week in Arlington National Cemetery – a decision that was made by Richard Ward Hanna, his nephew and namesake. Hanna, who lives in Gainesville, Florida, said his family didn’t talk about Ward much while he grew up, but he knows how incredibly respected the fallen sailor is in his hometown of Springfield.

“It’ll be very emotional,” Hanna said in early December. “I’ve been asked a lot, ‘Does this really give you a sense of closure?’ And for me personally, I wouldn’t so much say it’s closure. I think what’s meaningful is he’ll finally have a resting place that’s permanent that people will know about. And being a Medal of Honor recipient is an incredible thing.”

After the war, Ward’s name was recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with many others who were missing during World War II. A rosette will now be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

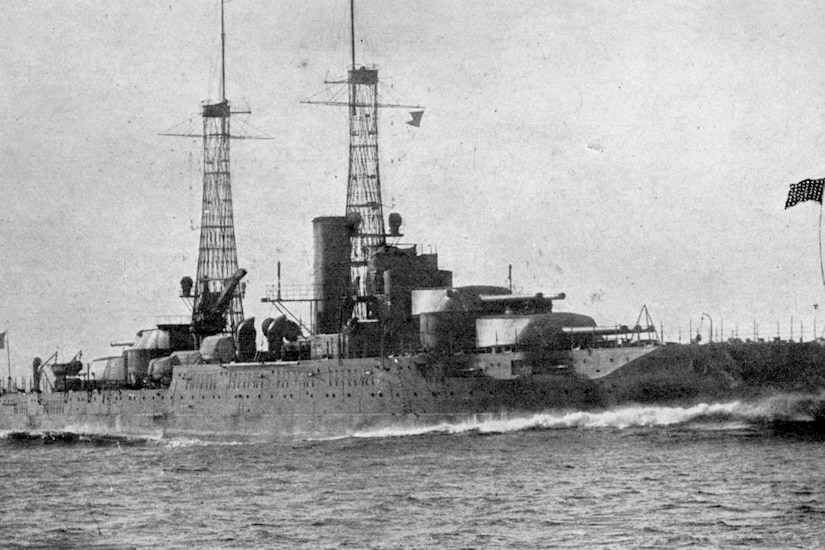

Even when Ward was missing for all those years, he was not forgotten. The Edsall-class destroyer escort USS J. Richard Ward, which commissioned in 1943 and was used throughout World War II, was named in his honor. Camp Ward at Farragut Naval Training Station in Idaho was also named for him, and in 1953, a Pearl Harbor baseball field was christened Ward Field. There’s an “in memory” marker for Ward at Ferncliff Cemetery in Springfield, Ohio, as well as an American Legion there that bears his name.